Linda’s Monthly Monday Morning Moaning’s for June 3, 2024

There are eighteen active lighthouses on the Washington coast line, three are standing but considered inactive, three have become automated towers, and two have been demolished. On September 16, Arcadia will publish ‘Lighthouses of the Pacific Coast’ the third in a series of four vintage postcard lighthouse books and here I hope to bring you a taste of what the state of Washington has to offer with three examples below.

Cape Flattery Lighthouse, in Neah Bay. The lighthouse was built on Tatoosh Island in 1857 in the northwestern point of the United States, as a navigational aid to mariners entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Because of thick fog and especially the strong currants ships could be carried toward the dangerous shores of Vancouver Island. Placing the light on Tatoosh Island allowed marine shipping to enter the strait at night. Tatoosh Island is a 20-acre rock ledge lying one-half mile off Cape Flattery. Because of its height from the water, being 100 feet, landing ships for restocking was a hazardous undertaking. A one-and-a-half story, Cape Cod style sandstone dwelling was built with two-foot-thick walls. The main floor consisted of a dining room, kitchen and living room. Four bedrooms were in the upper story. A 65-foot brick lighthouse tower was built in the center of the building. The first-order Fresnel lens, had a fixed white light with a visibility of 20 miles. In 1883 the telegraph was brought to the island by the longest cable hung, that stretched from the island to the mainland. In 1904 that cable went underground. 1932 had the first-order lens being downgraded to a fourth-order. By 1977 the lighthouse automated.

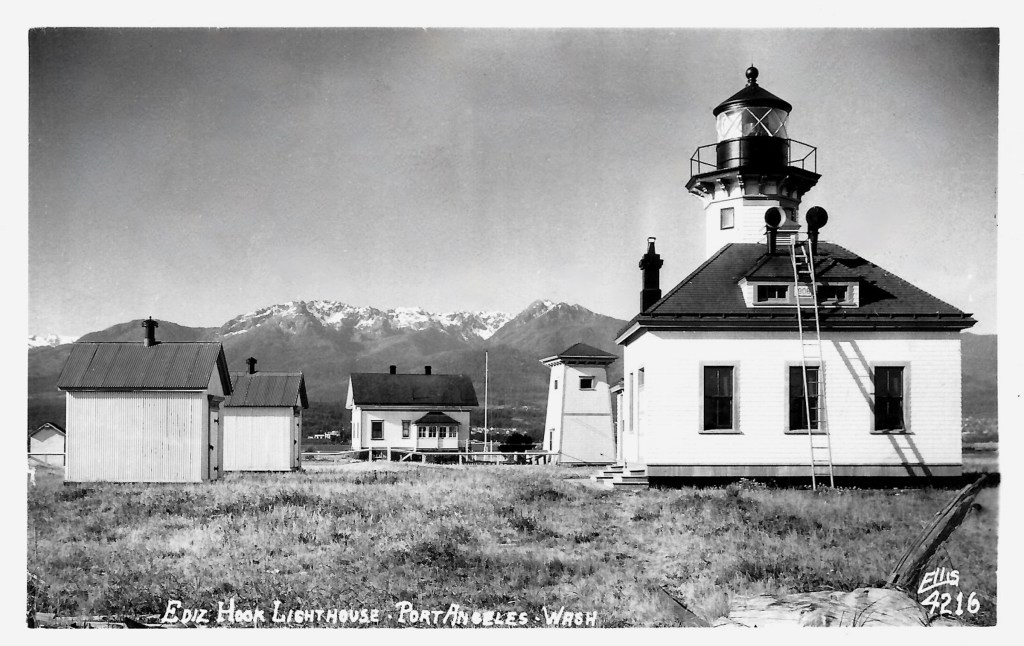

Ediz Hook Lighthouse, Port Angeles. With Port Angeles, the northwests deepest harbor, is a three-and-a-half-mile long sand spit, an accumulation of sand usually attached to land at one end, and called it Ediz Hook. President Lincoln n 1862 signed an order that the end of the spit be used for governmental purposes. In 1865 the original two-story school-house design lighthouse was constructed with a square tower at the end of the pitched roof. In 1885 a fifteen-foot fog bell tower was built with a one-and-a-half-ton bell that hung from the top beams of the structure. Using a clock mechanism, every fifteen seconds during foggy weather the bell would ring. The years would see changes to the fog bell to make the sound more effective. In 1908 a new a fog signal building with an attached octagonal light tower and a separate keepers dwelling was built at the station. The fifth-order Fresnel lens was removed from the old tower and placed in the new tower. A beacon was used to replace the second lighthouse, placed at a Coast Guard Air Station in 1946. The 1908 lighthouse became a private dwelling after being removed from the station area. The original 1865 light was demolished in 1939. This second lighthouse was destined to last only about forty years, when it was replaced by a modern beacon at the coast Guard Station in Port Angeles. The 1908 light was sold for use as a private residence after being removed by barge across the harbor.

North Head Lighthouse, Port Angeles. At the mouth of the Columbia River channel, mariners found that the Cape Disappointment Lighthouse was often obscured when approaching the river. Concern was great because of the many ship wrecks, along the peninsula. In 1898 the light was first lit with a fixed-white light, while Cape Disappointment Light, just two miles north would use an alternating light of red and white flashes. The new lighthouse on Cape Disappointment would be called North Head Lighthouse. The light was constructed of brick on a sandstone foundation, then using a cement plaster overlay. A 65-foot- tower with lantern room and a first-order Fresnel lens was brought from Cape Disappointment. Soon a keepers residence, two oil houses, barn, and duplex housing for the assistance keepers, would round out the light station. Being a light keeper at North Head Light meant getting used to a very remote and hard life. It helped when there were three keepers in residence to have work schedules of 8 hours at a shift. Usually one keeper worked from dusk till dawn, then others did the maintenance during the daylight hours to keep it in top working order. In 1937 the first-order lens, is changed for a forth-order lens, by this time electricity has been brought to the light station. Because of this being one of the windiest spots in the United States, for a short time a US Weather Bureau was built at the station, but would eventually close by 1955. The light was automated in 1961 and at that time the last light keeper would leave. The lighthouse was transferred to the Keepers of North Head Lighthouse group in 2012 for restoration purposes. North Head has remained the light station with all it’s original buildings still untacked.

On that ‘wee note’ till next month, Monday July 1st, 2024.

All post card images used are from the author’s collection.

Thank you for visiting and reading today. Please if you haven’t already, enter your email address in the subscription form below to receive my blog by email on the first Monday of each month. Thank you.